The farther you go, however, the harder it is to return. The world has many edges, and it's easy to fall off. - Anderson Cooper

16 September 2019, Ganvié

Hotel Germain 17,500CFA (R438)

The most notable thing about the residents of Ganvié is how at home they are on the water. This was made evident not only by observation, but by contrast with our clutzy and anxious boarding and unboarding of unstable water craft. From the tiniest tot to the most elderly woman, from the plump to the slender, all display an unconscious elegance as they glide in rhythmic silence across the lake, manoeuvring with practised ease through narrow channels between stilted homes, and past and between other craft, going about their daily business.

Ganvié is a town of (perhaps) 65,000 sited at the north end of Lake Nokoué opposite Cotonou which lies south of the lake. It is a town built, not on land, but on the lake itself. The town was founded during the slave trade when people took to the water to avoid being taken captive. Though some residents are Christian and others Muslim, most are adherents of the voodoo religion, recognised officially in Benin, with none of the negative connotations associated with it in the west.

We had arranged to meet the Hotel Germain shuttle at the Calavi peer at around 12:00. Our ride from Abomey to Calavi in a car with a shattered windscreen and tape holding the dash together, was a little fraught. We had agreed for our driver to collect us at 09:00, making it clear he had to carry additional passengers as is usual with collective taxis. He assured us he had put together a carload, but when we reached Bohicon where he was to collect his other passengers, they were departing in a rival vehicle. This made him rather bad-tempered (understandably, perhaps) and we had to wait an hour before his car was filled, one passenger joining us on the back seat, and two young men squeezing in discomfort onto the single front seat. And then he raced us in haphazard fashion to the Calavi peer, reaching it shortly after 12:00.

We took two tours of Ganvié: one late afternoon on the day we arrived, one early-morning on the day we departed, the former in a small canoe with wooden planks for sitting on, the latter in the larger motorised hotel shuttle. The lake, 20km wide, 11km long, is on average 1.5m deep. At times brackish, at times fresh, depending on the season, the lake is a rich source of fish, and fishing the main income source for the residents of Ganvié. Homes are generally constructed of wood and palm and stand above the lake waters, on occasion at a drunken angle, on wooden stilts; some homes and bigger buildings such as hospitals and schools, are more secure on concrete pilings.

Boats vary in size from canoe to public transport. The smaller boats are either built from curved wooden planks, or are traditional dugouts, made from a single hollowed tree trunk, always with a flat stern for sitting on while rowing or standing on while poling. We saw one exceptionally large dugout which our guide, Junior, son of Christopher, the hotel owner,* told us came from a tree grown in Nigeria. The larger boats, especially those used as collective taxis to Calavi and Cotonou, are motorised. Other boats are either poled or rowed; on open water a makeshift sail may be raised, made from sacks and other packaging, or a pretty cotton fabric. The rowing paddles are often shaped like the spade found in a deck of cards. When women peddle their wares to residents, they paddle between homes advertising whatever it is they have for sale, food or clothing or household goods or baskets, by calling out to residents, then paddle up to open doorways to exchange goods for cash. To keep their wares dry when rowing, they transfer the paddle from left to right to left again, not in front of their bodies, but twirled over their heads behind them, where any water drops fall harmlessly back into the lake.

We saw a boy aged four, alone in a canoe, rowing past us with ease, and passing beneath a low bridge by using his hands on its underside, and reversing into a slot between homes. He looked as if he had been doing just that for YEARS. And saw a man alone in a long boat with ten or more planks across it by way of passenger seating, poling at speed. He did this by placing his pole in the mud when standing at the front of the boat, then walking rapidly across the planks to the back of the boat, pushing all the while on the pole, then lifting it from the water and walking to the bow to start again. The speed he reached with this inherently unstable manoeuvring was astonishing.

We saw huts painted yellow and purple and green reflected in the lake, and people drawing fresh water from a well beneath the lake, and someone with a generator offering a charging service for cell phones and other devices of a modern world, and large tattoos on the backs and shoulders of older women, and people in large straw hats like the one lent me by the hotel.

Although government has tried to lease sections of the lake to fishermen from Ganvié, the residents have made it plain that the state has no right to intervene in fishing practices established by their ancestors. Patches of the lake “belong” to families living on the lake, and are passed on to their children. In these patches, fishermen “plant” dry branches or palm leaves. These create shady areas and provide food for fish, attracting them to places where catching them is virtually guaranteed. At the morning market, we saw a large boat transporting dry branches nearly knock a woman from her much smaller canoe.

By way of greeting, people called out “Yovu” (white) as we passed, and on occasion “cadeau” (gift). Few benefit in any direct way from the addition of gawping tourists into their watery world.

At 04:00 every morning, women gather in their boats at the morning market, selling food to fishermen and to other early commuters. They light their wares with a paraffin flame that throws an orange reflection into the rippling lake, and call out into the dark: I’m selling rice and beans OR bread and fried fish OR bananas… Some paddle in search of clients; others anchor their boats by pushing wooden poles into the sediment, one at the back of the boat on one side, one at the front on the other, and wait for clients to respond to their calls. Junior and our boatman parked the hotel boat in the hyacinth opposite the market and there a woman came at our request to sell us her bananas. As the light increased, sellers and buyers began to disperse, their voices drifting to us over the stilling waters. We had a real sense that thus have people been trading for millennia, and although in that sense it was entirely prosaic, it was moving and atmospheric to witness, unconsciously beautiful.

The hotel spoiled us with a great dinner buffet and tasty breakfast, then ferried us back to Calavi where we walked through the market to the main road to get a mini-bus to Cotonou and zamidjan (autocycle taxis) to our guesthouse.

*Christopher’s parents moved from Ganvié to Calavi, but Christopher, a translator by trade, opened the Germain on the lake. His oldest daughter is studying medicine; Junior is to begin a civil engineering degree later this year.

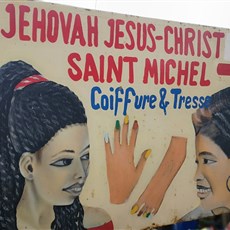

Leaving Abomey

Leaving Abomey

Leaving Abomey

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié

Ganvié morning market

Ganvié morning market

Ganvié

Calavi market

Calavi market

Calavi market

Calavi market

En route Cotonou